The Definitive Case against

Rev. Dr. Christiaan Kappes

Seventy-five years ago, Angelomorphic Christology or Angel-Christ theology was pretty much unknown. Its scholarly reemphasis and popular rediscovery has solved numerous alleged problems with interpretation of the Old and New Testaments from both a scholarly and popular point of view. This, like many other alleged issues with Angel-Christ, is at the heart of misunderstanding Justin Martyr today. Again: Angel of the Lord is Jewish-Hebrew and Jewish-Greek code for an aspect of God that comes to lower heavens and earth to visit and to convey a message. The Angel of the Lord is about a function so that the Hebrew angel (MLK) does not suppose that something is created or mortal or temporal but only that it functions as a messenger from God. This explanation among Christians was early and defined by Tertullian (Against Praxeas) as early as the late 100s AD. The main alleged problem stems from the Anglican divine Schaff and his mistranslation of Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 56:

[Justin:] I shall attempt to persuade you, since you have understood the Scriptures, [of the truth] of what I say, that there is, and that there is said to be, “another God”[1] and Lord subject to the Maker of all things; who is also called an Angel, because He announces to men whatsoever the Maker of all things— above whom there is no other God — wishes to announce to them (Κἀγὼ πάλιν· Ἃ λέγω πειράσομαι ὑμᾶς πεῖσαι, νοήσαντας τὰς γραφὰς, ὅτι ἐστὶ καὶ λέγεται Θεὸς καὶ κύριος ἕτερος ὑπὸ τὸν ποιητὴν τῶν ὅλων, ὃς καὶ ἄγγελος καλεῖται, διὰ τὸ ἀγγέλλειν τοῖς ἀνθρώποις).

The Greek hypo/ὑπό (subject to) is typically alleged to embrace subordinationism. Justin’s context of his thought on God confronts three angels on this question, challenging any Jewish reading Genesis, chapter 18. Notice that the new CUA translation, based upon the critical edition (that is, the scientific edition) of the Greek of Dialogue with Trypho.[2] The updated translation is far superior as to the preposition “subject to.” The newest translation reads: “There exists and is mentioned in Scripture another God and Lord under the Creator of all things.” The advantage of this translation is that it is reconcilable with Justin’s Jewish argumentation in Greek with the worldview of a Greek-speaking Jew of the second century. What do I mean?

Notice: “Creator of all things.” Where, I ask, in the Greek-Jewish Bible (Septuagint) and Greek commentators (here: Philo of Alexandria)[3] is the creator of things? Is he in heaven above or on earth below? In heaven there is God and on earth is the Angel of the Lord, identified thus:[4]

[Judges 13:21 (Septuagint)]: And the angel appeared no more to Manoah and to his wife: then Manoah knew that this was an angel of the Lord. 22And Manoah said to his wife, We shall surely die, because we have seen God (Hebrew: When the angel of the Lord did not show himself again to Manoah and his wife, Manoah realized that it was the angel of the Lord. 22 “We are doomed to die!” he said to his wife. “We have seen God!”)[5]

This is just one of many examples where God’s presence on earth in most ancient books of the Old Testament is often designated by Angel of the Lord. The Angel of the Lord is below God, in the heavens or on the earth, and visits under or underneath the heavenly throne.[6] The Angel of the Lord is visible in some way as sensible to the patriarchs and other Israelites. Hence he appears (as Philo the Jew and Moses Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed, relate to their imagination or mental phantasy).

Argument for the Grammatical: “Accusative of Position”

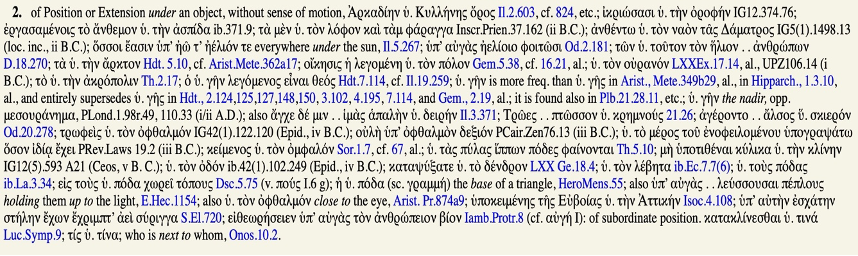

Hypo/ὑπό/Under is correctly used to translate the Biblical location: under the vault of heaven… God – when he is called Angel – is to be found under God’s throne (in heaven) or under heaven and this explains the accusative of place (in Justin’s dialogue about the Greek Jewish reception of the Greek Old Testament in the second century to Greek-speaking Jews). This explanation reflects very well the usage of hypo in the best Greek dictionaries (lexica):

Liddell-Scott dictionary above might easily interpret the Angel-Christ to be in some place underneath God in heaven and even literally “under the sun” or “under the earth.” Notice that a subordination interpretation is possible, but also, as I will argue a 1st-century and more likely interpretation meaning: “next to” or at “the right or left of,” which I will argue is the real meaning of Justin’s phrase.

Just like Justin Martyr’s argument to Trypho the Jew around AD 150,Philo the Jew around AD 50 explains that Jews hold for the three divine realities that appeared to Abraham to have three names, where the first is named: “Being” who corresponds to Justin’s “Creator” but it is the divine or God called: “Lord” who is seen physically (that is by a brain phantasy or imagery-vision in the prophet’s mind). Philo’s homily On the Godhead (Armenian/Greek retroversion) reads:

After this it is said: Three men stood above him (Genesis 18:2). . . . This [Creator] appears to his own disciple and righteous pupil surrounded on either side[7] by his powers, the heads of armies and archangels,[8] who all worship the Chief Leader in the midst of them (Isaiah 6:1–3). The One in their midst is called Being; this name, “Being,” is not his own and proper name, for he himself is unnamable and beyond expression, as being incomprehensible. . . . Of his two body-guards on either side, one is God (theos), the other Lord (kyrios), the former being the symbol of the creative, the latter of the royal virtue. Concerning the three men, it seems to me that this oracle of God has been written in the Law: I will speak to you from above the mercy seat, from between the two Cherubim (Exodus 25:21). As these powers are winged, they fittingly throne on a winged chariot [Ezekiel 1] over the whole cosmos. . . . In the midst of whom he is found [the text] shows clearly by calling them “cherubim.” [one at the right the other at the left] One of these is ascribed to the creative power and is rightly called God; the other to the sovereign and royal virtue and is called Lord. . . . This vision woke up the prophet Isaiah and caused him to rise.[9]

The two seraphim (in Isaiah 6:1-3) and two cherubim (in the temple on the ark of the covenant) are below or under the God on his throne and God’s mercy seat, respectively. The Angel of the Lord by definition is something that “appears” or is seen in is a vision in the prophets’ imagination/phantasy. Therefore, the Angel of the Lord is visibly below/hypo/υπο the location of the creator or God on his throne. The images of two cherubim-angels below the Mercy Seat are below the place whereon the Creator sits, so that God sits over or above the two cherubim (For Origen of Alexandria, in the tradition of Philo, these are the Angel and the Spirit). So, we cannot be dealing with Greek philosophical claims of subordinationism but rather Jewish language referring to the position of God and his angels in the Bible.

Because Justin Martyr uses Philo of Alexandria according to the critical or scientific edition of the Greek text, let us compare Justin’s source: Philo the Jew (around 50 AD), That the Worse is Wont to Attack the Better:

XLIV. Why, that the wise man is called the God of the foolish man, but he is not God in reality, just as a base coin of the apparent value of four drachmas is not a four drachma piece. But when he is compared with the living God, then he will be found to be a man of God; but when he is compared with a foolish man, he is accounted a God to the imagination and in appearance, but he is not so in truth and essence. (ὅτι ὁ σοφὸς λέγεται μὲν θεὸς τοῦ ἄφρονος, πρὸς ἀλήθειαν δὲ οὐκ ἔστι θεός, ὥσπερ οὐδὲ τὸ ἀδόκιμον τετράδραχμόν ἐστι τετράδραχμον· ἀλλ’ ὅταν μὲν τῷ ὄντι παραβάλληται, ἄνθρωπος εὑρεθήσεται θεοῦ, ὅταν δὲ ἄφρονι ἀνθρώπῳ, θεὸς πρὸς φαντασίαν καὶ δόκησιν, οὐ πρὸς ἀλήθειαν καὶ τὸ εἶναι, νοούμενος).

Just like the citation from Schaff and CUA above (I shall attempt to persuade you, since you have understood the Scriptures, [of the truth] of what I say, that there is, and that there is said to be, another God and Lord subject to the Maker of all things), we see that vocabulary and theme are similar here. Ancient people think that: a wiseman “ is and is said to be” God in comparison to a fool. But the suppose this due to “imagination and appearance.” This is the same kind of exposition of the Angel of the Lord. He is a wiseman that is thought to be God. However, says Philo, human beings are not really God even if they appear and are thought to be in our brains, since this does not correspond to their “essence/being” and “truth.” For his part, Justin repeats this phraseology but adjusts the Angel of the Lord to be God “in existence/being” and “is said to be God.” This ostensibly means that Jesus is – unlike Philo’s wisemen – merely a man but is God. This is exactly what both Philo and Justin would imply by someone below the heavens being and being called God by essence. When the Angel of the Lord by Justin is compared to God, he is found to be another divine or divine. This phraseology (rather unique in Greek) is under discussion by Justin and Trypho who both are using Philo the Jew’s works. An Angel of the Lord is both called and is God by both Justin and argued to be such by Philo above in On the Godhead (above).So, within a 1st-2nd century context, Justin is arguing that “there is” and “there is called” “divine” someone who in truth and this proven since he is the someone “below” the mercy seat (the angel of the Lord) and the divine being sent “below the heavens” where God is the highest physically imagined being and, for both Philo and Justin is the essentially or so-called ontologically highest being in the universe as well.

Since Justin Martyr (as per the critical edition in Greek) is thoroughly imbued with the Christology of the Epistle to the Hebrews in the Dialogue with Trypho, it is worthwhile mentioning that the Angel of the Lord Christ the High priest should in theory be paired with some aspect of himself that is lower than God in heaven ontologically (as people say) or as far as the dignity of some aspect of his being. Indeed, we find this in New Testament Christology:

there is some aspect of the Angel of the Lord that is lower (see Hebrew and Psalm: “you have made him a little lower than the angels”). Within 1st century Christology and Jewish exegesis this already makes sense that there is something even metaphysically lower (anything visible or that is lower than the high part of the heavenly throne/vault).

| Hebrews 2:5-9 | LXX Psalm 8:4-5: |

| For He has not put the world to come, of which we speak, in subjection to angels. 6 But one testified in a certain place, saying: “What is man that You are mindful of him, Or the son of man that You take care of him? 7 You have made him a little lower than the angels (ηλαττωσας αυτον βραχυ τι παρ αγγελους) You have crowned him with glory and honor, And set him over the works of Your hands. 8 You have put all things in subjection under his feet.” For in that He put all in subjection under him, He left nothing that is not put under him. But now we do not yet see all things put under him. 9 But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels, for the suffering of death crowned with glory and honor, that He, by the grace of God, might taste death for everyone. | What is man, that thou art mindful of him? or the Son of man, that thou visitest him? Thou madest him a little less than angels, thou hast crowned him with glory and |

Above, we see that there is an invitation by the Angel of the Lord beneath the place where the angels dwell and that Jesus’s flesh or human nature is somehow “less than” or “lower than” the angels. Really, we can take Justin’s “under” to mean that Jesus is underneath the heavenly throne and underneath the higher places where the angels dwell, or we take it in the sense that Jesus in his flesh is inferior to some power or virtue of angels (since flesh is corruptible or mortal or what not). It doesn’t really matter. The distinction between the divine and the non-divine aspect of Jesus was part of primitive Christology. Against either of these possibilities is the context of Justin who is trying to argue not an advanced Christology but something quite primitive (theologically) to a Jewish dialogue partner and he argues by interpreting three visible angels of Genesis 18 to be divine. How does Justin really help Trypho by using the term “under” since Trypho is clearly not a subordinationist in comparison to Justin (especially for today’s scholars)? In response, Justin’s citation from Genesis notes that the three Angels are “above” so that Abraham had to look up to see them (like Psalm 8:4). The Psalm 8:4 (above) reflects the primitive notion in Genesis that Angels are “above” humans. Angels of the Lord are located above Abraham and he is “under” them. Justin’s argument is that there are three angels and that the one of interest (the Christ-Angel) is located in position to, or in relation to, the Creator-Angel. Elsewhere, in his First Apology Justin makes sure to identify these three men as: Father, Son, and Spirit, as someone first, second, and third in an order (taxis). See Justin Martyr, First Apology, 13.3:

Our teacher of these things is Jesus Christ, who also was born for this purpose, and was crucified under Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judea, in the times of Tiberius Cesar; and that we reasonably worship Him, having learned that He is the Son of the true God Himself, and holding Him in the second place, and the prophetic Spirit in the third order, we will prove. For they proclaim our madness to consist in this, that we give to a crucified man a place second to the unchangeable and eternal God, the Creator of all; for they do not discern the mystery that is herein, to which, as we make it plain to you, we pray you to give heed. (Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν, τὸν σταυρωθέντα ἐπὶ Ποντίου Πιλάτου, τοῦ γενομένου ἐν Ἰουδαίᾳ ἐπὶ χρόνοις Τιβερίου Καίσαροςἐπιτρόπου, υἱὸν αὐτὸν τοῦ ὄντως θεοῦ μαθόντες καὶ ἐν δευτέρᾳ χώρᾳ ἔχοντες, πνεῦμά τε προφητικὸν ἐν τρίτῃ τάξει ὅτι μετὰ λόγου τιμῶμεν ἀποδείξομεν.)

Justin’s mention of three Angels and his belief that the Father, Son, and Spirit form an array or taxis, which is probably military in meaning due to his reference to the militant Angels of the Lord in Joshua, as elsewhere (like Philo). For example, in the Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 63, when identifying the Angel-Christ he not only equates the Angel of the Lord (Judges 13) with Christ as God but with the Angel-Warrior of Armies:

Listen, therefore, to the following from the book of Joshua, that what I say may become manifest to you; […] Joshua was near Jericho, he lifted up his eyes, and sees a man [compare Genesis 18: “three men”] standing over against him. And Joshua approached to Him, [..] And He said to him, I am Captain of the Lord’s armies: […] And Joshua fell on his face on the ground, and said to Him, Lord, what do You command Your servant? And the Lord’s Captain says to Joshua, Loose the shoes off your feet; for the place whereon you stand is holy ground [This is the Angel of the Lord on Sinai].

We now have sufficient context to understand the Jewish-Biblical references and Jewish mode of argumentation. The Angel-Christ is a military figure as well as an Angel who provides military strategy. In fact, Justin his Dialogue with Trypho (chapters 11 and 13) by noting: “He alone is God who led your fathers out from Egypt with a strong hand and a high arm” (viz., right hand) and ““And to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed (Isaiah 53:1ff)? We have announced Him as a child before Him.” In effect, the military arm of God, or Angel of the Lord, is nothing less than a warrior God on earth. In first-century Greek, when military men are arrayed in due order within a military unit, the word hypo takes on a military meaning, not a philosophical meaning or even a the typical “accusative of place” meaning: under. Instead, let’s take a look at first-century Greek used in a military context when three or more soldiers are lined up in array: We turn to the “how to be a general” (or Captain for the Old Testament) manual of the first-century Greek writer: Onosander (contemporary to Philo and near contemporary with Justin) in his Strategicus:

First arming the soldiers, he should draw them up in military formation that they may become practiced in maintaining their formation; that they may become familiar with the faces and names of one another; that each soldier may learn by whom he stands*** (τίς ὑπὸ τίνα) and where and after how many. In this way, by one sharp command, the whole army will immediately form ranks (ἐν τάξει). Then he should instruct the army in open and close order; in turning to the left and right (ἐπὶ λαιὰ καὶ δεξιά); the interchange, taking distance, and closing up of files; the division into files; the arrangement and extension of files to form the phalanx; withdrawing of files for greater depth of the phalanx; battle formation facing in two directions, when the rear guard turns to fight an encircling enemy; and he should instruct them thoroughly in the calls for retreat.

***one person next to another or one at the left/right of another: See the Liddell-Scott translation above: “next to whom.”

In effect, what Justin Martyr, within the context of his time, dialogue partner, religious texts, and imagery of military usage is committed to is a general of an array of angels.[10] These three angel appear in an ordered way to Abraham and they stand above him one next to the other so that we can see how future readings in the Old Testament by the Psalms, Jesus and Apostles altogether put Jesus to the right of the Creator-Captain and the Spirit to the left of the Creator-Captain who appears according to Justin to Abraham. The meaning of “hypo/next to” hear seems in a military, Jewish, and organization context to signify that the angels for Justin form in Genesis 18 one line with a central figure and another man at the left and the other man at the right hand. Jesus as Justin’s “other God” or “other divine one” (theos) is at the right of the Creator and is his equal in the army as soldiers of equal rank arrayed together. As such, there is no sense in which I need to admit that Justin’s Angel-Christ is either “subordinate to” or “under” the Creator in some sort of moral or so-called ontological sense. If anything the context argues them all to be of equal military rank.

Finally, immediately after the time of Justin, we see below that the anonymous Ps-Clement identifies someone claiming equality with God in both “existing” and “being called” divine (Just like the phraseology of Philo and Justin). Anyone who shares the creator’s rule or has a common name with him (theos) is equal to him. Each Angel of the Lord for Justin shares the common name “theos,” as too for the Jew Philo. Justin designates Philo’s God: “Being,” as: “Creator.” For his part, Ps-Clement (3rd century just after Justin), in chapter XXXVII, writes:

Whom to Know is Life Eternal. But if you art thankful, O man, understanding that God is your benefactor in all things, you may even be immortal, […] you are able to become incorruptible, if you acknowledge Him whom you did not know, if you love Him whom you forsook, if you pray to Him alone who is able to punish or to save your body and soul. Wherefore, before all things, consider that no one shares His rule, no one has a name in common with Him—that is, is called God. For He alone is both called and is God [Both Philo and Justin use this phrase in Greek]. Nor is it lawful to think that there is any other, or to call any other by that name. And if anyone should dare do so, eternal punishment of soul is his (οὐδεὶς αὐτῷ συνάρχει, οὐδεὶς τῆς αὐτοῦ κοινωνεῖ ὀνομασίας,τοῦτο ὃ δὴ λέγεται θεός. μόνος γὰρ αὐτὸς καὶ λέγεται καὶ ἔστιν, ἄλλον δὲ οὔτε νομίσαι οὔτε εἰπεῖν ἔξεστιν· εἰ δέ τις τολμήσειεν, ἀιδίως τὴν ψυχὴν κολασθῆναι ἔχει).

The Genesis-Angels for Justin share their rule with each other and thus they are all God or divine (theos) in common with him. According to this Jewish-Christian language – like Ps-Clement – this makes both the Creator and the “second God” of Justin potentially equal within the historical context of the first- and second-century interpretations of Angel of the Lord appearances.

CONCLUSION

The term “under” or “hypo” is not subordinationist within the register or Jewish-Greek usage of terms, since hypo references location (e.g., beth-el; the house of the Lord) of Philo’s Cherubim (cf. Isaiah 6:1-3) and God’ throne (a throne which the Son of Man can sit upon). In fact, hypo almost certainly is meant to convey: “next to” as in the Son of Man or Angel of the Lord (Seraph) at the right hand of the Creator. Thus, I offer a version of the Dialogue of Trypho retranslated:

Here [in Genesis where a row of three angels are mentioned] exists and is mentioned in Scripture another God [at the right of the middle angel] and Lord next to [at the right hand of] the Creator of all things.

Appendix: On the Usage of “Another God” and “Other God” by Justin Martyr

The critical edition of Justin’s works in Greek reveal that, with the exception of one minor citation from an historical book of the Deuterocanon,[11] Justin Martyr did not cite any of the Deuterocanonal books of the Bible to his dialogue partner Trypho. Furthermore, Justin used extensively Philo’s Questions and Answers on Genesis, as in the Appendix of the critical/scientific Greek edition:[12]

Trypho seems to represent a Jewish community that was, by and large, knowledgeable of Philo in both Alexandria and Rome. Since Trypho was originally from Palestine, and since Segal has demonstrated that the “two powers” debate or the Jewish arguments about whether there is “another God” existed in Hebrew discourse, then it is not surprising that Trypho and Justin are dialoguing – both from Palestine/Syria areas – about this doctrine that must have been available to both of them. Their Greek-Jewish tradition of interpretation often (but not always) reechoes in later Rabbinic literature like the third-century Mishnah. As Segal first identified, “second God” is a Jewish (not Christian) tradition that predates Philo, since Rabbis who are almost certainly unacquainted with him subsequently battle this tradition in Hebrew (and less so in Aramaic). Let us set up the argument as follows:

- The Old Testament books that were canonized after Rabbi Akiva (c. 150), in their Greek versions, do not condemn the Greek technical term: “another God” (heteros theos), but generally oppose the terminology of “other gods” (heteroi theoi).[13]

- Opposition to Jewish theology favoring “other God” terminology can be clearly found first in late-deuterocanonical literature that translates Hebrew or Aramaic texts:[14]

- LXX Judith 8:20-21 (KJV; 114-77 BC?): “But we know none other god (ἕτερον θεὸν), therefore we trust that he will not despise us, nor any of our nation.”

- LXX Baruch 3:36 (KJV; translated 165-1 BC): This is our God (theos), and there shall not be another (heteros) be accounted of in comparison of him

- LXX Daniel 3:96 (both Old Greek and Theodotian; translated after 120 BC + 2nd c. AD): Wherefore I publish a decree: Every people, tribe, or language, that shall speak reproachfully against the God of Sedrach, Misach, and Abdenago, shall be destroyed, and their houses shall be plundered: because there not another God (heteron theon) who shall be able to deliver thus.

This reaction in these texts could be read to date the “second God” vocabulary as early as 2nd century BC. Philo’s tradition is apparently in opposition to the traditions of these translators who are precluding the vocabulary. However, Philo does not cite the broader Deuterocanon as Scripture, possibly being closer to Origen’s testimony of Jewish canon in Alexandria. As such, he naturally is a representative of the “second God” or “heteros theos” Jewish tradition without preoccupation of the broader LXX tradition opposing the term.

Because Justin Martyr is dialoguing with someone who takes Philo’s works and tradition as authoritative, we notice that he uses a canon that does not reflect what we know of Alexandrian Judaism (without the broader selection of Judith-Baruch-Daniel)[15] and therefore he argues for the “other God” tradition since it is acceptable or authoritative for Philo and has not yet presumably been formally condemned as in the Mishnah and Rabbinic commentaries. This is key to a passage of Philo in On Questions and Answers in Genesis II:

(62) Why is it that he speaks as if of some other god (ἑτέρου θεοῦ), saying that he made man after the image of God, and not that he made him after his own image? (Genesis 9:6). Very appropriately and without any falsehood was this oracular sentence uttered by God, for no mortal thing could have been formed on the similitude of the supreme Father of the universe, but only after the pattern of the second deity, who is the Word of the supreme Being; since it is fitting that the rational soul of man should bear it the type of the divine Word[16]; since in his first Word God is superior to the most rational possible nature.[17] But he who is superior to the Word holds his rank in a better and most singular pre-eminence, and how could the creature possibly exhibit a likeness of him in himself? Nevertheless he also wished to intimate this fact, that God does rightly and correctly require vengeance, in order to the defense of virtuous and consistent men, because such bear in themselves a familiar acquaintance with his Word, of which the human mind is the similitude and form.

“It is clear that Philo uses and approves of the term ‘second God’ which the rabbis later would find repugnant, because it allows him to maintain the truth both of his philosophy and of his scripture.”[18]

What I propose as knew is that the translator Theodotion (See Daniel 3:96) proves definitively (viz., philologically) the existence of Rabbinic opposition to the notion of “another God” (heteros theos) by the mid-2nd century AD. Furthermore, given a very late dating of the LXX Judith-Baruch-Daniel, we can suppose increasing opposition to this terminology in the last decades of the BC era.

So, is Justin Martyr a subordinationist by reference to “another God”? Thus far, the answer must be “clearly no.” Instead, both men born in the area of Syria-Palestine are familiar with the “other God” tradition that has not been condemned by Rabbis yet, though it has been implicitly chastised by translators of the Deuterocanon, including the contemporary Jewish translator Theodotion. Still, ought we not think that “other God” theology can be taken as dividing God into superior and inferior parts? That is, doesn’t this create for Jews of the time a higher and lower God of power and thus implicitly commit Jews to subordinationism? The answer must still be negative. Justin Marty clearly signals that he is dealing with Biblical motifs, not metaphysics. He contrasts explicitly Philonian “another God” (heteros theos) theology against “other God” (allos theos) theology in his opening remarks to Trypho in chapter 11:

[Justin:] There will be no other God (allos theos),[19] O Trypho, nor was there from eternity any other existing, but He who made and disposed all this universe. Nor do we think that there is one God for us, another for you, but that He alone is God who led your fathers out from Egypt with a strong hand and a high arm. Nor have we believed in any other (for there is no other), but in Him in whom you also have believed.[20]

Here, “other God” means that some other being or separately or independently existing or co-existing thing is anathema. This is due to a common Greek-speaking Jewish common reception of LXX Isaiah 43:10, so dear and important to 1st-century Jews and Christians: Some “Other God (allos theos) has not come before me and there shall not be one after me. I am God,” and LXX Isaiah 45:21: “I am God, and there is no other (allos).” Philo, who embraced the “another God” (heteros theos) also rejected the “other God” (allos theos). For example, Philo rejects “other God” in Allegorical Interpretation III, 26.82:

XXVI. (82) But Melchisedek shall bring forward wine […] For reason is a priest, having, as its inheritance the true God, and entertaining lofty and sublime and magnificent ideas about him, “for he is the priest of the most high God” (LXX Genesis 14:18). Not that there is any other god (allos theos) who is not the most high; for God being one, is in the heaven above, and in the earth beneath, and there is no other besides Him” (LXX Deuteronomy 4:39).

Again, Philo taught in On the Birth of Abel and the Sacrifices Offered by Him and by His Brother Cain, 92: “neither is there any other god (allos theos) of equal honor with him.” Justin likewise emphasizes that nothing else divine exists even from eternity. This excludes any sort of dual principle, one higher and the other lower, since there is only one principle or one source of deity for both Jews and Christians. However, using Angel-Christ theology, Justin identifies the Jewish interpretation that God’s Angel or “strong hand and high arm” are the means on earth by which God manifested himself. This is explicitly made clear to be Jesus, who is the “another God” or “another divine reality” (heteros theos). Let us see again the same chapter in Justin:

Isaiah himself said, when he spoke thus: “The Lord shall make bare His holy arm in the eyes of all the nations, and all the nations and the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of God.” (Isaiah 52:10) […] “And to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed (Isaiah 53:1ff)? We have announced Him as a child before Him, as a root in a dry ground. He has no form or comeliness, and when we saw Him He had no form or beauty; but His form is dishonored, and fails more than the sons of men. He is a man in affliction, and acquainted with bearing sickness, because His face has been turned away; He was despised, and we esteemed Him not.”

For Justin and for Jewish exegesis, the right arm of God is the Angel of the Lord. This Angel of the Lord is not some “other God” (allos theos) but is “another divine” (heteros theos) or “another God” in Philonian terminology. As such, Justin commits himself to the absolute unity of God so that whatever God’s arm is, or his word is,, or his angel is, it cannot mean a co-eternal and different being but rather some eternal aspect of God that must be identified as there with the “Father” and “Creator” but which is means by which the Father and Creator comes down to the lower heavens and earth to reveal himself to created angels and the human race.

In the next century, in Palestine the extreme unitarian Heraclides and the loose Trinitarian Origen will both agree (around AD 244-249) that indeed Philo’s “heteros theos” is an orthodox expression to indicate the relationship between the Father and the Son:

Origen said: “Jesus Christ, ‘though he was in the form of God’ (Philippians 2:6), while still being distinct from God in whose form He was, was God before He came into the body: yes or no?” Heraclides said: “He was God before.” Origen said: “Was He God before He came into the body or not?” Heraclides said: “yes, He was.” Origen said: “Was He another God (heteros theos) from this God in whose form He was?” Heraclides said: “Obviously distinct from the other and, while being in the form of the other, distinct from the Creator of all.” Origen said: “Is it not true, then that there was a God, the Son of God and only begotten of God, ‘first born of all creation’ (Colossians 1:15), and that we do not hesitate to speak in one sense of two Gods, and in another sense of one God?”[21]

As Heraclides and Origen discuss the Philonian idea first taken philologically from Exodus 34:14, they seem to agree with Philo that the Word is both distinct from the Creator/Father but also God in every way. As such an extreme unitarian and a robust Trinitarian were able to agree on the orthodoxy of this phraseology:

Thus we do not fall into the opinion of those who, cut off from the Church, have fallen prey to the illusory notion of unity (monarchias), abrogating the Son as distinct from the Father and also, in effect, abrogating the Father; nor do we fall into the other impious doctrine which denies the divinity in Christ. What, then, is the meaning of such sacred texts as: “Before me no other God (allos theos) was formed (Isaiah 43:10)? … “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). (Dialogue with Heraclides,4.5-13)

In conclusion, “another God” is a technical term condemned by LXX books, but which Justin Martyr never cited to Trypho against the term because no general condemnation was authoritative in Greek for the Palestinian Jews like Trypho. So, Trypho must have been familiar with Philo’s “second God” or “other God” Jewish theology, as embraced by Philo, and was known too by Justin who is a reader of Philo, and is acceptable to Trypho. The reason that this vocabulary is not subsequently embraced by Christians and the church Fathers lies in the fact that it is suspect and even condemned by the received versions of Baruch, Judith, and Daniel. Justin’s usage betrays acceptance of its technical orthodoxy as understood by the Philonic school of interpretation.

The Theological Influences in the Reception of LXX Exodus 34:14:

“For you shall not offer worship to another God (theôi heterôi), for the Lord, who is God, he is a jealous name and he is someone jealous.” 200 BC Alexandria

LXX Baruch: anti-heteros theos 165 BC Palestine(?)

LXX Isaiah: anti-allos theos‘Ca. 145 BC Alexandria

OG Daniel: anti-heteros theos 135-120 BC Judea

LXX Judith: anti-heteros theos 114-77 BC Israel

Philo: pro-heteros theos + anti-allos theos AD 50 Alexandria

Trypho-Justin Martyr: pro-heteros theos+ anti-allos theos AD 135 Palestine-Syria

Thedotion Daniel: anti-heteros theos AD 190 Judea

Clement: anti-heteros theos+ anti-allos theos AD 180 Alexandria

Origen: Dialogue with Heracleides: Pro-heteros Theos+ anti-allos theos around AD 250 Palestine-Alexandria

[1] See Segal, Two Powers in Heaven…, (Leiden, 1977), 177: “Philo can use the same argument and the same term “second God” (Greek: deuteros theos, Latin: secundus deus).” I provide the passage in question in the Appendix below.

[2] Justin Martyr, Dialogue avec Tryphon: Éditin critique, traduction, commentaire,ed. Philippe Bobichon, Paradosis: Études de littérature det de théologie anciennes 47.1-2 (Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg, 1993).

[3] Nonetheless, Alan Segal, Two Powers in Heaven…, (Leiden, 1977), 43, interprets the most ancient Hebrew and Aramaic texts of the Rabbi’s (typically dated to the centuries after Philo as supporting Philo’s claims that his interpretations reflect mainline Jewish ideas about God having both manifestations on earth as aspects of God, as well as personified attributes.

[4] See Segal, Two Powers in Heaven…, 76-79, for the Hebrew-Rabbi tradition that heaven and earth refer to two Gods; thus, even the Semitic traditions had schools taking the Scriptures in the sense of Justin Martyr.

[5] Slight emendation of Manoe to Manoah is my own.

[6] See Segal, Two Powers in Heaven…, 168:

Philo’s understanding of the word “place” [beth] is logos. Therefore, the mystic, here Moses, does not see God himself, but the logos, “the place where God stands,” who is manifested in the narration at Ex. 24:10 f. as a human figure astride the world.

[7] So the first militaristic “Seraph is next to the throne” that might be rendered in military terms: “o Seraphin hypo ton thronon.”

[8] See below that 1st-century military ordering of these two angels means that there is a line of equals standing in array with one angel at the right and left or next to each other of the central angel not below each other!

[9] I have simply taken this from Bogdan Bucur’s article “I saw the Lord…”, who cites: Folker Siegert, “The Philonian Fragment De Deo: First English Translation,” Studia Philonica 10 (1998): 1–33. The Greek terms are taken from Siegert’s Greek retroversion in his original publication, Wohltätig verzehrendes Feuer, quoted above. See also Francesca Calabi, God’s Acting, Man’s Acting: Tradition and Philosophy in Philo of Alexandria (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 73–110.

[10] For the Hebrew context that supports Justin’s and Trypho’s militaristic reading of the Angels of the Lord, see Segal, Two Powers in Heaven…,33-35. Here the Military Leader God (and Angel) who was seen at Sinai can be equated to the “Old Man” in white in Daniel 7:9 and his interplay with the “Son of Man.”

[11] 1-2 Ezrah is apparently accepted by Trypho in his Jewish community. See Philippe Bobichon, Index Scripturaire, in Dialogue avec Tryphon: Édition critique, traduction, commentaire,Paradosis: Études de littérature det de théologie anciennes 47.1-2 (Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg, 1993), 2:1040.

[12] Ibid., Index Auteurs…,in Dialogue,2:1101.

[13] An interesting exception almost seems to occur in LXX Exodus 34:14, a central text for Jews: “For you shall not offer worship to another God (theôi heterôi), for the Lord, who is God, is a jealous name and he is jealous.” Both to onoma/the name and ho theos/God are together jealous. Does this mean that there is “one” and “the other” or God and his name who are jealous? Philo never cites nor alludes to this passage in his works. This strange redundancy would not be lost on Greek readers who would note that Angel of the Lord is also the Divine Name or the Name that dwells in the Temple. Here Philo and others would see that the terminology “other God” as applied not to idols (which must be burnt) but only to the Divine Name. the “Divine Name” or “Angel” is therefore the “other God.” For the equivalence of “Angel of the Lord” and “Divine Name,” see Charles Gieschen, Angelomorphic Christology…, (Leiden, 1998), 70-78.

[14] For dating and information on each LXX book, I consulted J. Aitken (ed.), T&T Clark Companion to the Septuagint (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

[15] Canticle of Canticles is not quoted to Trypho, but the controversial Ezekiel is. Esther and Sirach are not cited – though a contested book until this time. This means that the Jewish tradition behind Origen-Eusebius and St. Athanasius’s Epistle 39 are probably unrelated to Justin and Trypho’s agreed upon Jewish list of books acceptable for debate.

[16] See Segal, Two Powers in Heaven…, 162: Philo’s terminology bears striking resemblance to the early rabbinic designation MQWM for God. His concept of logos is similar to the rabbinic doctrine of God’s Shekhinah, each of which is often used to explain the same difficult scriptures.

[17] Ibid.: When “place” refers to something divine revealed to man, as it did in the passage above, for Philo, it may mean God’s image, His logos. It is, in fact, impossible for man to see God and live (Ex. 33:20). However, Moses and the elders see the image of God or everything “that is behind me” (Ex. 33:23). These are equivalent to the logos which as a second God can also be given the title “Lord.” (kyrios = YHWH).

[18] Segal, The Two Powers in Heaven…, 165.

[19] Justin condemns “allos theos” also in Dialogue 50.1, 56.4-11.

[20] I have slightly modified “trust” into “belief.”

[21] Origen, Dialogue of Origen with Heraclides and His Fellow Bishops on the Father, the Son, and the Soul, ed. R. Daley, Ancient Christian Writers 54 (New York, 1992), 58.

One thought on “Justin Martyr’s “Subordinationism””