The following is taken from Chosen People Answers’ article, Psalm 22 and “They Pierced My Hands and Feet”.

Brian Crawford

Psalm 22:1, 16–18, English Standard Version

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from saving me, from the words of my groaning? … For dogs encompass me; a company of evildoers encircles me; they have pierced my hands and feet—I can count all my bones—they star and gloat over me; they divide my garments among them, and for my clothing they cast lots.”

כָּאֲרִ֗י יָדַי וְרַגְלָי

Leningrad Codex, Psalm 22:16 [17]

כארו ידיה̇ ורגלי

Nahal Hever 5/6HevPsalms, Psalm 22:16 [17]

What’s in a Word?

In the sixteenth century, Christian publisher Daniel Bomberg was commissioned to publish the first Mikraot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible) using the newly invented printing press. Reportedly, as he was preparing the proofs for Psalm 22:16 (v. 17 in Jewish Bibles),[1] one of his Jewish proofreaders drew his attention to a single word: כארו (ka’aru). This word would not do, the Jewish man told Bomberg. If the word were not changed to כארי (ka’ari), “no Jew would buy copies of his Hebrew Bible.”[2] There is only one letter in question between the two options: the final Hebrew letter should be either a ו (vav) or a י (yud). One might not think that a single Hebrew letter would be such cause for concern, but in this case, the proofreader’s perception of the Jewish community was likely correct. The inclusion of the vav would make the Psalm teach something remarkably similar to the crucifixion of Jesus. Bomberg took the advice, and Jewish publishers have retained the word כארי (ka’ari) ever since.

By no means, however, has the debate on the word been settled, even to this day. In their recent commentary on Psalm 22:16, biblical scholars Rolf Jacobson and Beth Tanner write, “[This] line may be one of the most debated in all of Scripture.”[3] They count more than ten monographs and multiple scholarly journal articles that attempt to explain how one should understand the verse. For example, from 1997 onwards, there has been a flurry of articles published in the Journal of Biblical Literature with punning titles about the guesswork involved in solving the verse’s quandaries.[4]

As one might also guess, the driving force behind this controversy often involves a religious debate relating to belief in Jesus. Christians have often supported a translation of “they pierced my hands and feet,” whereas Jews have supported readings relating to a lion.[5] Over the history of this debate, each side has fallen into the unhelpful trap of accusing the other side of willful mistranslation, tampering, and conspiracy over this verse—accusations which we find to be speculative bias and harmful to Jewish and Christian relationships.

A selection of various Jewish and Christian translations of the second half of the verse illustrates the disagreement:

Jewish translations:

1. JPS (1917): “like a lion, they are at my hands and my feet.”[6]

2. NJPS (1985): “like lions [they maul] my hands and feet.”[7]

3. Stone (2013): “Like the [prey of a] lion are my hands and my feet.”[8]

Christian translations:

1. NASB (1995): “They pierced my hands and my feet.”[9]

2. ESV (2016): “They have pierced my hands and feet.”[10]

3. NIV (2011): “They pierce my hands and my feet.”[11]

4. NAB (2010): “They have pierced my hands and my feet.”[12]

The Jewish translations are united in their understanding of a lion being present in the verse, but they differ on the verb. Christian translations have no lion but rather the verb “pierce,” and their translations are all alike. These two options (like a lion/they pierced) are directly tied to whether the Hebrew word underlying the translation has a vav or a yud as the final letter. Even these two translation options might seem to be much ado about nothing, if it were not for the history of Christian usage of this verse in conversation with Jewish people.

Psalm 22:16 and the Pierced Messiah

Psalm 22:16 is never quoted, mentioned, or alluded to in the New Testament. Although the verse frequently shows up in contemporary Christian lists of Messianic prophecies, the New Testament never directly cites Psalm 22:16 as a prophecy about the Messiah. The New Testament’s omission of the verse means there is no controversy or danger for the New Testament’s credibility if the disputed word is translated as “like a lion” rather than “pierced.” Nothing in the New Testament hangs on the verse, unlike passages such as Isaiah 53 or Psalm 110:1, which are quoted repeatedly by Jesus’ followers as prophecies fulfilled by him.

Despite the omission of the verse from the New Testament, it understandable why this line in the Psalm became so attached to Jesus. While Psalm 22:16 is not quoted in the New Testament, the following verse (v. 18[17])[13] is quoted or alluded to during the crucifixion narratives (Matt. 27:35, Mark 15:24, Luke 23:34, John 19:24), and Jesus himself cried out the opening line of the Psalm as he was dying on the cross (Matt. 27:46, Mark 15:34).[14] Moreover, the chief priests spoke the words of Psalm 22:8 when they mocked Jesus during the crucifixion (Matt. 27:43).[15] The entirety of Psalm 22 appeared to be at the forefront of the Gospel writers’ minds as they chronicled the crucifixion.

Reflecting on these New Testament interpretations of Psalm 22, early Gentile followers of Jesus began reading the entire Psalm in light of Jesus’ crucifixion. Rather than a direct prophecy, the Psalm was interpreted as a patterned foreshadowing, where everything that David experienced in the Psalm would be repeated and exceeded by the Son of David, Jesus the Messiah. As Gentile followers of Jesus, these readers were not reading the Hebrew text of Psalm 22, but rather the Greek Septuagint (LXX) version of the Psalm, which was translated by Jewish people at least two centuries before the crucifixion. As they read, their eyes became transfixed on the following phrase:

ὤρυξαν χεῖράς μου καὶ πόδας[16]

English: They pierced/dug through my hands and feet.

The violence of crucifixion was unmistakable in this phrase, these early Gentile followers of Jesus reasoned. They wondered how could this not be a foreshadowing prophecy of Jesus’ brutal death? Or, how could this not be primary evidence that Jesus was the Son of David, the one who repeated the events of David’s life and brought them to completion?

Already by the second century CE, Gentile Christian authors like Justin,[17] Tertullian,[18] Irenaeus,[19] and Barnabas[20] were citing Psalm 22:16 as primary evidence for the Messiahship of Jesus. Moreover, these early authors often quoted the verse when addressing reasons why the Jewish people should accept Jesus as the Messiah of Israel. The verse was often paired with Zechariah 12:10, in which God speaks about being pierced by Israel on some occasion. This early interpretive tradition eventually became the standard Christian reading of Psalm 22:16, a tradition that holds to this day.

In sum, the translation, “pierced,” has been irrevocably attached to a Christian understanding of the verse, and the translation, “like a lion,” has often been seen as the Jewish understanding of the verse. Any Jewish Bible, like Bomberg’s, that would print anything approaching the Christian understanding would likely not sell many copies to Jewish readers.

Messianic Jews, however, would beg to differ with the current status quo. As Jews who believe in Yeshua, they reject the dichotomy between “Christian” and “Jewish” readings of the verse.[21] The standard of truth on the verse should not be determined by one’s religious community, but rather by the evidence of the manuscripts of Psalm 22 themselves. Thus, when the Messianic Jewish Tree of Life Bible translates the verse, it reads, “They pierced my hands and my feet,” with a footnote for “or, is like a lion.”[22] This solution prefers the reading of “pierced” while also giving honor to the Masoretic tradition in the footnote.

It is unfortunate that there is a Christian/Jewish divide on this translational question, because the most likely and accurate answer—כארו, ka’aru, “pierced”—may be traced to the manuscript evidence itself. For the remainder of this article, we will investigate the manuscripts in question, thereby defusing any accusation that “pierced” is a mistranslation or Christian invention.[23] If David really intended “pierced” in his Psalm, and God intended David’s life to be a foreshadowing of Messiah, then Psalm 22:16 may be a powerful indicator of Yeshua as the Messiah.

The Numerous Masoretic Hebrew Manuscripts of Psalm 22

Before we can begin with our investigation on Psalm 22:16, we need to get one thing out of the way: there is no one Hebrew text or even Masoretic text to consult for the Psalm.

Many Hebrew Bibles, such as ArtScroll’s Stone Edition, which is popular in Orthodox circles, simply reproduce the Leningrad Codex, the best and most reliable complete Hebrew manuscript we have of the Tanakh. They do not let the readers know about alternative manuscripts that have different Hebrew readings. It may be a surprise to some that there are different manuscripts with variant readings for the Psalm. We would encourage such readers to consider our Textual Criticism 101 article to orient themselves with the process of investigating the Hebrew manuscript tradition.

Although the Leningrad Codex is our most reliable Hebrew manuscript, it is problematic to treat it as free from error. There are many other Hebrew manuscripts—also faithfully and meticulously copied by Jewish scribes—that contain consonantal differences when compared with the Leningrad Codex.

When scholars want to determine whether there are textual differences for any particular verse in the Tanakh, they primarily consult two sources: Eighteenth century textual scholar Benjamin Kennicott’s collation of textual variants,[24] and the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS).[25] The BHS prints the standard Leningrad Codex Hebrew and adds footnotes to words that have different spellings or renderings in other Hebrew manuscripts. For Psalm 22:16[17], the BHS lists alternate readings for “like a lion.” The footnote for the word כָּאֲרִי (ka’ari, “like a lion”) reads:

pc Mss Edd כארוּ, 2 Mss Edd כָּרוּ cf 𝔊(𝔖) ὤρυξαν, α´ ἐπέδησαν, σ´ ὡς ζητοῦντες δῆσαι[26]

If that made no sense to you, have no fear. Welcome to the cryptic world of textual criticism, where reading a sentence is a multilingual treasure hunt of translations and acronyms. This cryptic line may be understood to mean,

Although most Masoretic manuscripts have כָּאֲרִי (ka’ari), between 3–10 Hebrew manuscripts read כארוּ (ka’aru) and two read כָּרוּ (karu), and one should also consult the ancient Greek Septuagint, the Syriac, Aquila, and Symmachus translations as well.

While it is true that most Hebrew manuscripts have “like a lion,” there are a few that do not. And those few—with the words כארוּ (ka’aru) or כָּרוּ (karu)—each mean “pierced” or “to dig out.”[27] Perhaps it is now clear why no one should be accorded credibility when they claim that “the Hebrew says ka’ari.” That is an overstatement of the manuscript evidence for “like a lion.”

In addition, it is important that the most recent edition of BHS was published in 1997. It is missing one of the most important ancient Hebrew versions of Psalm 22, which was published for the first time after the BHS went to print.[28]

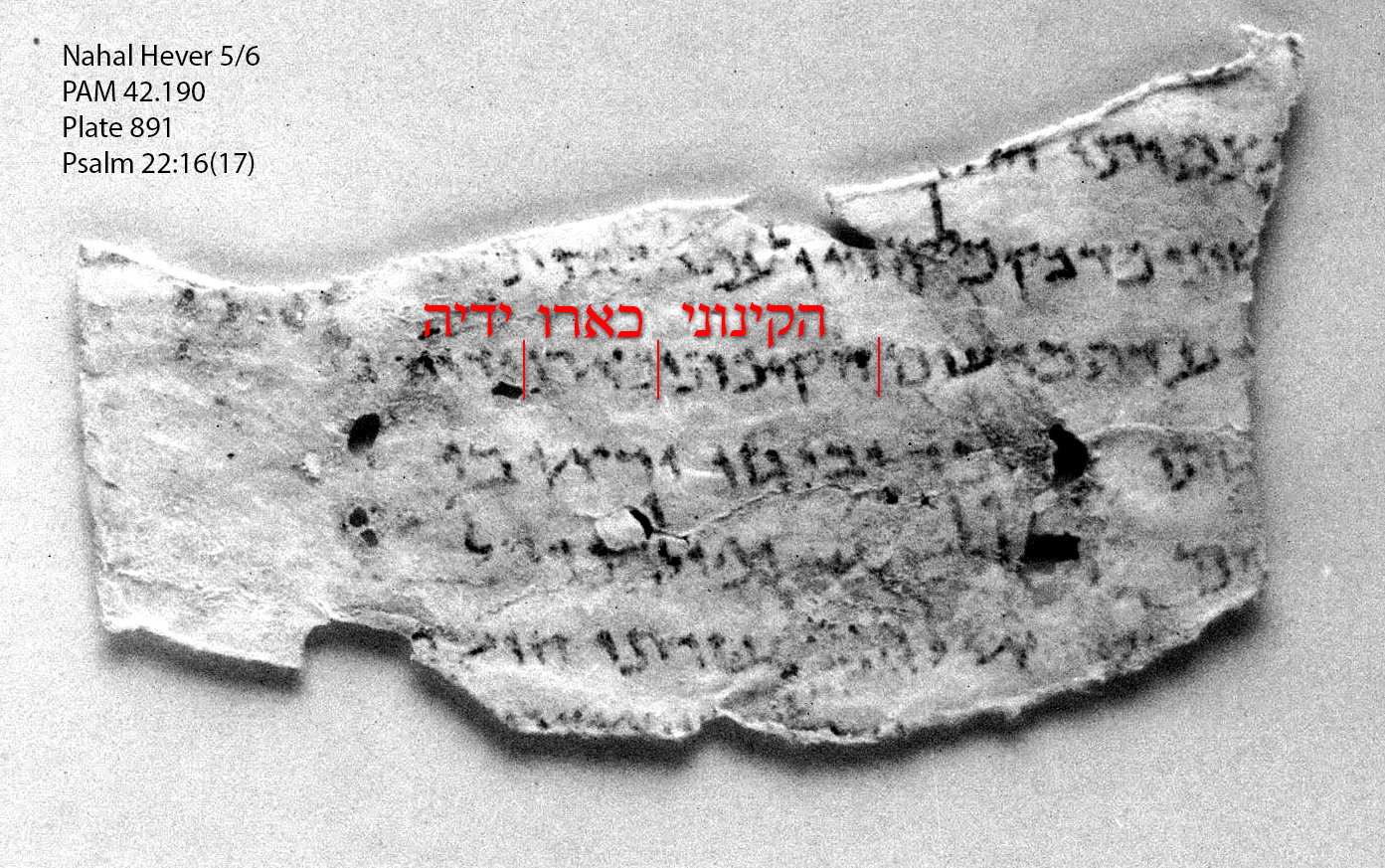

Evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Earliest Hebrew Manuscript for Psalm 22

In the late 1990s, a series of fragments from the Nahal Hever caves were published. These caves are in the mountains on the west side of the Dead Sea, and they may have been produced by the same community as the famous scrolls found in Qumran. The scrolls date from the mid-first century CE, meaning that they predate the Leningrad Codex and other medieval Hebrew manuscripts by nearly a millennium. One of the fragments, named “5/6HevPsalms,” contains Hebrew text for Psalm 22:16. A facsimile provided by the Leon Levy Digital Dead Sea Scrolls Library is below, with our notes added:

Figure 1 – 5/6HevPsalms, Plate 891, M42.190, The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-280844

This fragment may be badly faded (especially in the original facsimile provided on the official Dead Sea Scrolls site), but imaging software brings out the letters sufficiently. The result is that the text in this ancient scroll does not have כארי (ka’ari), but כארו (ka’aru). The last letter is definitively a vav, and not a yud. It does not say “like a lion” but rather, “they pierced/dug out.”

In 1999, the authors of The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible, an English translation of the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls, were among the first to publish the ramifications of this find:

Psalm 22 is a favorite among Christians since it is often linked in the New Testament with the suffering and death of Jesus. A well-known and controversial reading is found in verse 16, where the Masoretic Text reads “Like a lion are my hands and feet,” whereas the Septuagint has “They have pierced my hands and feet.” Among the scrolls the reading in question is found only in the Psalms scroll found at Naḥal Ḥever (abbreviated 5/6ḤevPs), which reads “They have pierced my hands and my feet”![29]

In sum, this nearly 2,000-year old Hebrew manuscript—the oldest available for Psalm 22—produced before followers of Jesus ever could tamper with the text, clearly has a verb that matches closely with the sense of one’s hands and feet being violently pierced. This text also matches the Hebrew found in several much later medieval Hebrew manuscripts. Based on the Hebrew manuscript evidence alone—outside of any Jewish or Christian messianic debates—there is good reason to support the word “pierced.”

Additional Linguistic Reasons to Reject “Like a Lion”

In our discussions above, we focused on the evidence for the consonantal Hebrew text of Psalm 22:16. This evidence may be reasonable enough on its own to reject the “like a lion” translation. However, there are additional reasons, beyond mere manuscript evidence, that provide support for accepting “pierced” instead.

The Comprehension Problem with “Like a Lion”

First, the Hebrew ka’ari (כָּאֲרִי) in contemporary Hebrew Bibles, derived from the Leningrad Codex, does not make any sense. A literal, wooden, no-added-words translation of the key phrase with ka’ari is:

כָּאֲרִ֗י יָדַי וְרַגְלָי

“Like a lion my hands and my feet”

There is no verb in the phrase, leading to confusion. Hebrew prose often implies the English verb “to be” (is/are), so one could suppose that this phrase should be supplied a missing “to be” verb:

“Like a lion [are] my hands and my feet”

This addition solves the verb problem, but it does not assist the reader much with comprehension. There is some comparison between a lion and hands and feet, but this comparison is not at all clear. As it stands, the Masoretic majority reading with ka’ari is unintelligible. Multiple scholars have pointed this out: “This yields little sense for the rest of the line as there is no verb.”[30] “It remains harsh and drawling so far as the language is concerned.”[31] The text includes an “unorthodox use of grammar and syntax.”[32] The confusion over the meaning of the phrase is reflected in various Jewish translations, which solve the problem by adding extra words. The previous Jewish translations given above are now repeated, but with the added non-Masoretic words in red:

1. JPS (1917): “like a lion, they are at my hands and my feet.”

2. NJPS (1985): “like lions [they maul] my hands and feet.”

3. Stone (2013): “Like the [prey of a] lion are my hands and my feet.”

The JPS added the verb “are” and a preposition of location, “at,” which has an unclear signification itself. The NJPS brings out its verbal idea clearly with “they maul.” The Stone Edition adds a new subject, “prey,” resulting in a comparison between “prey” and “my hands and my feet” rather than with a lion. These added words solve the intelligibility problem, but they are not actually in any Hebrew manuscripts. Although the idea of a lion in this verse matches the presence of animals in other verses of the Psalm (worm, bulls, lion (vv. 13, 21), dogs, oxen), it is implausible that this benefit outweighs the cost of a phrase with no verb and no clear meaning behind the comparison being made.

Each of the solutions in the modern Jewish translations accept an incomprehensible Hebrew phrase as the standard and are thereby forced to fix the unintelligibility with their own creative solutions, none of which agree. A better solution, based on the Hebrew manuscript tradition, is to reject the “like a lion” reading because it is so incomprehensible.

Ancient Versions of the Line Have Verbs and No Lion

The word in the Leningrad Codex, כָּאֲרִי (ka’ari), is composed of a comparative prefix (כָּ) with a singular noun (אֲרִי). The resulting translation is “like a lion.” This grammatical construction (prefix + noun) is an outlier among all ancient versions of the verse, with the exception of Targum Psalms. Instead, the ancient translations of this line, whether produced by Jewish or Christian translators, understood the word in question to be a plural verb.[33] For example:

· Septuagint (LXX), third century BCE, Jewish: “They pierced/dug out (ὤρυξαν[34]) my hands and my feet.”

· Aquila’s first translation, second century CE, Jewish: “They put to shame (ᾔσχυναν[35]) my hands and feet.”

· Aquila’s second translation, second century CE, Jewish: “They bound (ἐπέδησαν[36]) my hands and feet.”

· Symmachus’ translation, second century CE, Jewish: “like those who seek to bind (ὡς ζητοῦντες δῆσαι) my hands and feet”

· Jerome’s translation, fifth century CE, Christian: “They have dug (foderunt[37]) my hands and my feet.”

Although these translations vary in their meaning, each has a plural verb in place of “like a lion.” None of them include any idea of a lion in their translation, meaning that they did not see ka’ari in their Hebrew manuscripts as they translated. Only one ancient translation, Targum Psalms, included a lion, but it included a plural verb as well:

· Targum Psalms, unknown dating, third century CE?, Jewish: “They bite my hands and feet like a lion.”[38] (נכתין היך כאריא אידי ורגלי)[39]

Apparently, the Hebrew manuscript tradition during these early centuries included a plural verb (“they bite”), but at some point, the plural verb was supplanted by ka’ari. The Greek and Latin translations are witnesses to the early verbal tradition, and Targum Psalms is representative of a transitional phase where the translator attempted to combine both a verbal and noun-based translation. By the time of the Masoretic period, the noun (כָּאֲרִי, ka’ari) had supplanted the verbal tradition as the standard Jewish understanding of the verse. Even so, several Hebrew manuscripts with verbal forms (כארוּ or כָּרוּ) remained in use.

Two of the translations, Aquila’s second version, and Symmachus, included the idea of the hands and feet being “bound.” Scholars have pointed out that this translation may also be explained if the Hebrew behind these translations was כארוּ (ka’aru). If Aquila and Symmachus had the Arabic cognate of kwr in mind, it would explain their translations, since the Arabic word means “to bind.”[40] Old Testament scholar Brent Strawn summarizes, “The minimum amount of change to the [Masoretic Text] if one emends כארי to כארו and relates the latter to Arabic kwr, and various other indicators, ‘they bind’ might have the interpretive edge in making sense of Ps 22:17b as it now stands.”[41] This is a plausible option, but it is dependent upon using an Arabic cognate instead of understanding the word through Hebrew. We find that to be helpful in explaining Aquila and Symmachus’ translations, but less than ideal to explain David’s original meaning in Hebrew.

It is very unlikely that the original Hebrew word penned by David was כָּאֲרִי (ka’ari), because all ancient versions understood there to be a verb, rather than a noun, for that word. It is more likely that there was a Hebrew verb for that word, a verb that confused some translators and led to different interpretations. In light of the Hebrew manuscript evidence available to us, the most likely verbal candidate that would explain these phenomena is the Hebrew word כארו (ka’aru). If we give the word’s Hebrew etymology the most weight (which we believe is most appropriate), rather than that of an Arabic cognate, the verb translates as “they pierced.”

Conclusion: Dispelling Mistranslations and Conspiracy Theories

Who knew that a single letter could cause so much trouble? In this investigation, we have illustrated several lines of manuscript and linguistic evidence that make ka’aru (כארו, “pierced”) the most credible of the options. The support for this option includes:

1. Early Hebrew manuscript support for ka’aru (“they pierced, dug”) in the Dead Sea Scrolls and in multiple Masoretic Hebrew manuscripts

2. Early Greek translation support for “they pierced” in the Septuagint

3. “They pierced” is more comprehensible than “like a lion my hands and feet.”

4. “They pierced” agrees with the plural verb grammatical structure found in all ancient translations (Septuagint, Aquila, Symmachus, Vulgate).

It should be noted here that these four points have nothing whatsoever to do with Jesus, the New Testament, or Christian bias. As we have stated, there is no verse in the New Testament that lives or dies based upon our determinations here, although it is highly likely that Yeshua saw his crucifixion experience through the lens of the entirety of Psalm 22. Instead, our investigation has remained close to the manuscript and linguistic evidence, never straying into personal and religious accusations. Our argument does not include a fifth point, which could say something like, “Jewish people corrupted the text so it would not point to Jesus.” Just like there is no evidence for Christian conspiracy theories on Psalm 22:16, there is no evidence for Jewish conspiracy theories here.[42] Not only is there no evidence for Jewish tampering with the text, but it is additionally unlikely that a conspirator would introduce a grammatically unintelligible phrase into Scripture as if it were a benefit.

If a conspiracy is not afoot on this verse, then what explains the problems here? In our opinion, it was a simple mistake, mindless and innocent. The difference between “like a lion” and “they pierced” in Hebrew is a single stroke of a pen. Make the stroke short—that is, a י (yud)—and we have “like a lion.” Make the stroke long—that is, a ו (vav)—and we have “they pierced.” All it would have taken was one hand-slipping copyist accidentally writing a yud instead of a vav. If that one manuscript was copied into daughter manuscripts, then we could conceivably end up with the results we see in the manuscript tradition.[43]

Why did the “lion” reading take such precedence in Jewish usage, such that the older readings were forgotten? We can only speculate here, because we have no window into how the popularity of ka’ari grew over time. However, if there were two options before a Jewish scribe, and one word was actively exploited by Gentile Christians to point to Jesus, whereas the other word was not, all things being equal, the scribe was likely to choose the one that the Gentile Christian did not prefer. In her article on the psalm, religious studies professor Kristin Swenson wrote,

Probably in an attempt to avoid the association with Jesus, Greek-speaking Jews eschewed the LXX in favor of Aquila’s and Symmachus’s readings of the verse…. The word כארי, “like a lion,” which was eventually accepted by the Masoretes as the best text, may have gained popularity from a Jewish reaction to the Christian reading.[44]

Is this true? We cannot know based on the historical record we have available to us. However, it is certainly plausible that an innocent mistake in the textual tradition became magnified and grew in popularity in Jewish circles because of its utility in avoiding arguments in favor of Jesus.

Whether or not religious bias led to the common Masoretic reading of the verse, manuscript evidence ought to triumph over cherished interpretations that are demonstrably incorrect. If the evidence shows that “they pierced my hands and feet” is the most likely rendering of the verse, then readers should go where the evidence leads.

Footnotes

[1] We will use the Christian verse numbering for the remainder of this article, since this will enable functioning verse popups with our default English Standard Bible translation.

[2] Cited in Gregory Vall, “Psalm 22:17B: ‘The Old Guess,’” Journal of Biblical Literature 116, no. 1 (1977): 48. For this story, Vall cites D. P. Drach et al., Sainte Bible de Vence (27 vols.; Paris: Cosson, 1827–33) 9.464.

[3] Nancy deClaissé-Walford, Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth LaNeel Tanner, The Book of Psalms, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2014), 235.

[4] Vall, “Psalm 22:17B: ‘The Old Guess,’” 45–56; John Kaltner, “Psalm 22:17b: Second Guessing ‘The Old Guess,’” Journal of Biblical Literature 117, no. 3 (1998): 503–6; Brent A. Strawn, “Psalm 22:17B: More Guessing,” Journal of Biblical Literature 119, no. 3 (2000): 439–51; Kristin M. Swenson, “Psalm 22:17: Circling Around the Problem Again,” Journal of Biblical Literature 123, no. 4 (2004): 637–48; James R. Linville, “Psalm 22:17B: A New Guess,” Journal of Biblical Literature 124, no. 4 (2005): 733–44.

[5] We disagree that the camps are defined by Judaism or Christianity. Messianic Jews, that is, Jews who believe in Jesus, illustrate how there are Jews who accept the “pierced” translation for some of the reasons included in this article.

[6] Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures According to the Masoretic Text (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1917), v. Ps 22:17.

[7] Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures Jewish Publication Society (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1985), v. Ps 22:17.

[8] Nosson Scherman et al., eds., The Stone Edition Tanach, 3rd ed., ArtScroll Series (Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 2013), 1453.

[9] New American Standard Bible: 1995 Update (La Habra, CA: The Lockman Foundation, 1995), v. Ps 22:16.

[10] The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), v. Ps 22:16.

[11] The New International Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), v. Ps 22:16.

[12] The New American Bible, (Washington DC: Cofraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., 2010), https://classic.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm+22&version=NABRE

[13] “They divide my garments among them, and for my clothing they cast lots.” Psalm 22:18

[14] “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Psalm 22:1)

[15] “He trusts in the Lord; let him deliver him; let him rescue him, for he delights in him!” (Psalm 22:8)

[16] Septuaginta: With Morphology, electronic ed. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1979), v. Ps 21:17.

[17] Justin Martyr, 1 Apology 35, 38, Dialogue with Trypho 97–98, 104.

[18] Tertullian, Against Marcion 3.19, 4.42, On the Resurrection 20, Answer to the Jews, 13.

[19] Irenaeus, Demonstration 79.

[20] Pseudo-Barnabas, Epistle of Barnabas 5:13.

[21] See Michael Rydelnik, “Textual Criticism and Messianic Prophecy,” in The Moody Handbook of Messianic Prophecy, ed. Michael Rydelnik and Edwin Blum (Chicago, IL: Moody Publishers, 2019), 69.

[22] Messianic Jewish Family Bible Society, Holy Scriptures: Tree of Life Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2015), Ps 22:17.

[23] Tovia Singer makes the “mistranslation” charge against Christians in Tovia Singer, Let’s Get Biblical, New Expanded Edition (Forest Hills, NY: Outreach Judaism, 2014), 1:37. For another mistranslation charge that the verse was “strategically manipulated,” see Asher Norman, Twenty-Six Reasons Why Jews Don’t Believe in Jesus (Los Angeles, CA: Black White & Read, 2008), 253–55.

[24] Benjamin Kennicott, Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum : cum variis lectionibus, vol. 1 (Oxonii : Typographeo Clarendoniana, 1776), http://archive.org/details/vetustestamentum01kenn.

[25] Gérard E. Weil, K. Elliger, and W. Rudolph, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, 5. Aufl., rev. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997). Gérard E. Weil et al., Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, 5. Aufl., rev. (Stuttgart, Germany: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997).

[26] Weil et al., 1104.

[27] For examples of the root כָּרָה (karah), see Gen. 50:5, Psalm 7:16, Prov. 16:27. Ludwig Koehler, Walter Baumgartner, and M. E. J. Richardson, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, ed. Johann Jakob Stam (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2000), s.v. I כרה. There is no Hebrew root כאר, which one might expect for the other variant, כארוּ. However, there is no need to assume an error in this word, since alephs (א) were often added before the Masoretic vowel pointing system to assist with vocalization (called mater lectionis). The word with the aleph inserted is the same as כָּרוּ (karu), meaning, “they dug.” Keil and Delitzsch point to a parallel example of how רָאֲמָה (ra’amah) in Zechariah 14:10 is an expansion of רָמָה (ramah) with an added aleph. Carl Friedrich Keil and Franz Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1996), 5:200; Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, The Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1951), s.v. כוּר.

[28] As of this writing (2023), the Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ), an update of the BHS, has not yet had its volume on the Psalms published.

[29] Jr. Martin Abegg, Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English (New York, NY: HarperOne, 1999), v. Ps 22.

[30] Linville, “Psalm 22:17B: A New Guess,” 733.

[31] Keil and Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament, 5:200.

[32] Swenson, “Psalm 22:17: Circling Around the Problem Again,” 641.

[33] For the ancient textual variants, see Frederick Field and Origen, Origenis Hexaplorum Quae Supersunt Sive, Veterum Interpretum Graecorum in Totum Vetus Testamentum Fragmenta. (Oxford, UK: E typographeo Clarendoniano, 1875), 2:119, https://archive.org/details/origenhexapla01unknuoft.

[34] Walter Bauer et al., eds., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000), s.v. ὀρύσσω.

[35] Bauer et al., s.v. αἰσχύνω.

[36] Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon: With a Revised Supplement, ed. Sir Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie, 9th ed. (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1996), s.v. ἐπιδέω.

[37] William Whitaker, Dictionary of Latin Forms (Logos Bible Software, 2012), s.v. Fodio.

[38] Kevin Cathcart, Michael Maher, and Martin McNamara, eds., The Aramaic Bible: The Targum of Psalms, vol. 16 (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2004), v. Ps 22:17.

[39] Targum Psalms Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon (Hebrew Union College, 2005), v. Ps 22:17.

[40] Kaltner, “Psalm 22:17b: Second Guessing ‘The Old Guess,’” 503–6.

[41] Strawn, “Psalm 22:17B: More Guessing,” 448.

[42] We would appreciate the transparency, however, if a Jewish translation would include a footnote with “pierced” as a valid interpretive option.

[43] Biblical archaeologist Randall Price and Christian theologian H. Wayne House concur: “There is no evidence, as some have contended, that Jews or Christians tampered with the text. It is more probable that in one of the manuscripts used by the Masoretes the ink had degraded on consonant waw so that it was read by a scribe as a yod, resulting in the word being read as a noun rather than a verb.” Randall Price and H. Wayne House, Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017), 155.

[44] Swenson, “Psalm 22:17: Circling Around the Problem Again,” 638–39.